|

I finished teaching my first week with students. The week tested me in a way that I’ve never been tested as a teacher--I don’t even think my first week of my first year was this hard.

And I was teaching middle school at the time. The running theme of my week was a constant series of “roll with it” moments. There was zero certainty, and my plans were constantly uprooted and I had to figure out how to “make it work” (the only wonderful thing about this is that every time I said “make it work” I imagined a supportive, yet no-nonsense Tim Gunn standing next to me eyeing my peculiar choice of using velour for an evening gown when that is just not what you do). This whole week of teaching was one “that is just not what you do” sort of week. But within the chaos and tumult, I began to notice myself living in the uncertainty differently. And there were actually some moments where maybe I was like the contestant on Project Runway who managed to dazzle Tim Gunn with a salmon velour evening gown. Over the weekend, I watched a rerun of a talk show that featured Brene Brown. Her message to viewers: learn to be okay with uncertainty. And that’s what inspired me to begin this series. I’m not going to promise this post weekly because, you know, uncertainty. But this year, I want to use my blog as a space to share how the uncertainty of the year is transforming me as a teacher. And since this blog is all about how to enter into learning, I’m going to model bravely and vulnerably how to get on the on-ramp for this year. (Even if I am rerouted by multiple detour signs along the way). So, in no particular order, here are things that went sideways that actually turned out to be pretty decent. I got moved to teach a huge section to a lecture area instead of my classroom. (and the lecture area had no technology, and you know, this whole year is basically digital). There are two ways this sideways moment went in a way that it needed to go in. On my way down, I saw a hall monitor trying to help a student who was struggling to keep it together while trying to show a student where to go. I took the lost student for him. She was wearing a Black Lives Matter shirt. As she went to her room, I told her to have a great day, and “I like your shirt.” She smiled and went on her way. Later, our secretary saw her and did the same. We both agreed, kids who wear BLM shirts need to know we see them. I’m glad I went a different route that day. In the lecture area, my ninth graders were, in short, amazing and patient. That whole image of my being a teacher who has it together was totally shattered as we worked through the kinks of the no technology thing. And you know what, they were unphased and understanding. If a kid couldn’t get the link to work, they asked for help. I would help them, and we moved on. I think we tend to fear moments like this in our classroom. To an extent, it's probably why I've avoided some digital resources. Takeaway: If your kids have a device, create a Zoom meeting link to share. Then share everything on your screen with them. We managed to get through our lesson, collaborate through Jamboard and begin to develop some class norms. And if you get diverted, you might just end up getting where you needed to be. I realized some materials I had developed were redundant while teaching. (so with my students, we began changing it) Context: I teach a course where I train students to be writing consultants, and in the first week, we begin to unpack some of our values. It’s a really important day because it sort of frames our whole year together. The first few years I taught this course, it was important that I had a clear vision because after all, I was going to be the one who was here for the long haul. As my small group of consultants and I went through our notes about the values, one of the kids said “this kinda feels similar to the value we just talked about.” And he was right. The distinction between the two was incredibly fuzzy because they were just so interconnected! So we began to brainstorm about a new fourth value, and then the next group of consultants spent some time thinking about it too. Even though this was not what I intended, it was better. It gives my consultants a way to see their voice in our values. Takeaway: being vulnerable and admitting something wasn’t quite right wasn’t painful. None of my students scoffed. If anything, it became a powerful way to show them that the work of being a writer is vulnerable and involves being open to feedback. I’m always talking about the habits of mind of a writer. Instead of telling them, showing them was a way to establish this important norm. And it created a natural and organic way for my two groups of consultants to have a purpose to meet when we have our first “virtual Wednesday” day next week. I realized that parents don’t expect perfection or that we have this all figured out. (really, they just want us to know they are here for their children) I ended my day on Friday reaching out to a few families to talk about our plan for academic support. (Context: in addition to teaching ELA 9 and working with peer consultants, I am also a MTSS Student Support Coach the other part of my day). This week, our team spent some time organizing a schedule for support. Like a lot of districts, we have students who are hybrid and in-person part of the week and students who are 100% virtual. Did I also mention, I really only have two periods of the day to do this work? I have to admit, I was a little nervous to begin the phone calls, worrying that families would be upset that we couldn’t do more. I think it’s a common feeling that all of us have right now as teachers: we are worried we aren’t doing enough. Well, if you need to read this, here it is: stop it. You are doing enough. You are doing a lot. Takeaway: Even though I didn’t have all the answers to the questions that the parents had, they weren’t upset. In both cases, the parents were extremely grateful that someone had reached out to them to let them know that their child wasn’t going to go unnoticed. With each parent, I made a plan for support. For one family, it’s a regularly scheduled appointment over zoom. For the other family, it’s knowing that I’m ready for support when the first writing assignment rolls around. Parents and students want to feel noticed right now. They do not need you to have this all figured out. They just want to know you care about them. What I’ll Hold Onto From This Week

Onward to week two!

2 Comments

By this point in the year, most students are ready for texts that present nuance and force them to consider complex topics. Not only are they ready for this challenge, most are up for it. It’s April, after all, and most students have hit their stride.

But, what about the few students who are not quite ready to tackle a tough text? How do you challenge the majority who are ready and ripe for complexity, while responding to your two to five readers who need more support and direction? A good reading intervention begins in a classroom where reading and readers are valued and thoughtfully considered. While I’m fortunate to work with a team of interventionists, I realize that not all districts have this as a resource. These ideas are all one-teacher required. Create a Body of Multimedia Texts Recently, I worked with some freshmen who were examining a collection of primary source documents about prosperity and poverty in 1950s America. The groups of history teachers who designed this collection found a variety of sources that made the topic accessible for all students. Some of the sources were dense, like an excerpt from Michael Harrington’s The Other America, while others were more accessible like a photograph of an opulent suburban supermarket. One student started with the images first, and using this background knowledge, he was able to move onto the more challenging text by Harrington. Others were able to jump right to the text. While others simply examined the images as their source work. Here, images played a key role. They are an entry point for students because they make challenging content accessible. The images do not diminish the complexity either. Reading a visual text for readers at all levels is an important 21st century literacy skill. NCTE defines literacy in the 21st century broadly, and when students have an opportunity to examine a topic across multiple text types they can effectively synthesize complex ideas. Student- Selected Indy Reads While this does not directly address that tough text you’ve just assigned, giving students daily reading time with books that they select helps to build stamina in a way that is particularly helpful for an underperforming reader. When faced with complex texts, some readers do not have the stamina to even begin them. Complex texts require that a reader sustain reading over a period of time. And no matter what level the reader, daily reading is a high-yield practice for all students. All readers grow from a daily reading practice. Many of my students actually end up really enjoying reading when they find the right book. If you want students to even glance at a whole-class text, you need to establish a healthy reading culture where an underperforming reader can make reading a habit. Want some ideas for some high-interest young adult books? Check out this, this and this. Build in Time to Confer with Readers Reading time is something that many perceive as silent and independent so much so that in some places it’s still called “Silent Reading Time” just like it was when I was a kid. And yet, it’s talk that so often transforms adequate readers into robust readers. Getting to all students may feel challenging, but conferring daily with students while they are independent reading or when they read a class-assigned text will help you to suss out who’s reading and who’s “reading”. Conferring also gives you the opportunity to make any adjustments to what students are reading and clarify key content for students. Conferring time can even be used as reading intervention time to reteach skills from class or to respond to a specific skill gap. Sometimes I model how to monitor comprehension using sticky notes with my students. Then I ask students to go back and explain their thinking when we confer. Modeling how to monitor comprehension is a quick, high-yield strategy to use with readers. Conferring time is all about asking the right questions. Here are some questions that will help you to gauge engagement and comprehension:

The answers to these questions will provide you with data on a student, and if you are tasked with progress monitoring a student, this chart created by Harvey Daniels and Nancy Steineke can be a helpful way to capture what you’re noticing about a student. Getting Students to the Home Stretch Though some of your students may not struggle, these ideas benefit all students. All students grow from conferring, reading a collection of texts and daily reading time. When students leave our rooms, these are the practices that can sustain reading routines over the summer and into the next school year. By Lauren Nizol and Hattie Maguire

When writers are writing, it looks messy. Punctuation is off, sentences run on and on, ideas jumble together with little cohesion. That’s true for adult writers, beginning writers, and everyone in between. Unfortunately, when writing goes home and parents try to help out, that messiness is often tough to navigate. Many parents have preconceived ideas of what writing should look like. They are certain that their child isn’t a good writer and struggle to see beyond the technical aspects of writing (by the way, it takes a lot of teacher training to read sentences without punctuation for meaning). Many parents also may recall learning grammar like we did-- using diagrams and worksheets. These parents are certainly well-intentioned, but when the red pen comes out at home, young writers get frustrated. Parents need help finding the right kinds of words to talk to their children about writing. As parents ourselves, we get it. It is hard to see past the errors in your own child’s writing. Parents need an on-ramp for good writing conversation, so we created a resource to get them started. Some questions to try out:

A few things to remember:

But What About Grammar? Many parents would be surprised to learn that language instruction has moved away from traditional approaches that may include learning parts of speech and completing worksheets. Instead, language usage (or “grammar”) is most effective when taught within the context of a writing assignment. Instead of teaching students how to add commas as punctuation through a worksheet, much of the instruction has shifted towards students learning a language move and being able to apply it to their writing in real time. Research has proven that getting students to see how a writing convention impacts meaning is a far better way to instruct language. As a result, students see conventions as a choice that has an intentional purpose rather than something to memorize. Parents Matter Writers need audiences that go beyond their teacher. Parents are a natural audience because they know their child’s voice better than anyone. When students are able to share their writing with an important adult in their life, they find ways to consider an audience beyond their teacher. Riding the Waves: How I'm Surfboarding My Way to Break By Lauren Nizol My seven-year-old made up a song when he was four that sticks to this day. He likes to stand up when we pull into our driveway and pretend that he is surfing while he sings, “I’m surf-boarding, if you’re happy to know!” We really don’t know how it started, and admittedly--it’s a little weird since we have never surfed and we live in mid-Michigan (not exactly a local attraction for us). And I’ll be the first to admit that the song’s meaning is a little muddled (is he happy he’s surfing or does he want me to be happy that he is? Either way---it’s become an endearing quirk). But then, it struck me that my son’s jingle is a reminder that our students will each march to the beat of their own “Pa rum pum pum pum.” Our job is to find ways to respond to them with glad tidings and joy. We can’t look at behavior that seems out of place and immediately dismiss it. As the MTSS coordinator in my district says---”all behavior is communicating something.” Giving Grace to a Grinch Earlier this holiday season, my husband and I took our boys to see The Grinch. It was a lovely update, complete with a detailed character backstory about a boy Grinch who never felt included in Christmas. Cue empathy and understanding for a character with despicable behavior. At the end of the movie (SPOILER ALERT), in spite of the Grinch stealing Christmas, the Who-ville community still finds it in their hearts to welcome him to the dinner table. The Grinch is so moved that he changes his behavior and for the first time in his life, he enjoys Christmas. This month, I’ve noticed some buzz on eduTwitter and NCTE Village about how teachers can gain perspective when students exhibit challenging and "grinchy" behaviors. Many teachers are quick to refer to these weeks between Thanksgiving and Christmas as a long haul (I know that I do). We get very worried that a snow day (at least in Michigan) may thwart our well-laid out plans. We stress about reviewing enough before the assessments. And we are working hard to not bring planning or grading home with us over break. Sometimes when we are busy barreling through the curriculum, we forget that some of our students are stressed about other things: college admissions, navigating the holidays with divorced parents, or maybe worrying about being invited to hang out with friends over break. I know that sometimes I forget that I process stress as an adult; our students, though, don't always have these skills. (I have to remind myself that I've had at least twenty more years on them to practice managing stress). Andy Schoenborn shared on NCTE Village that it helps for teachers to "Remember you are teaching students, not a curriculum. Be responsive to them, not it." When teaching becomes focused on what students need rather than what we want to teach, we are able to connect with students who act out. After all, the Grinch stopped being "grinchy" when someone finally noticed he was in pain and included him. On that same note, Jennifer Wolfe puts it best when she explains: "Remember: No child wakes up in the morning hoping to fail. Somewhere, down inside, they want you to notice them. Help them. Smile at them. Love them." The most important way that we can extend grace in our classrooms is to realize that pain is not a place where any kid wants to be. Our role as teachers isn't to take away that pain, but we can provide a space as inclusive as Who-ville. #QTIP (My New Favorite Acronym) Last week, there was a great thread that started on @TeachMrReed’s feed. When students present challenging behavior, @TeachMrReed remembers to QTIP: Quit taking it personally.  This thread resonated with me because I can remember back to my first year of teaching when one of my students got so angry that he threw a chair. It's been so long that I can't recall now what he was angry about. When the counselor came to debrief the situation with me, she told me something that sticks with me to this day---kids present challenging behavior where they feel safe. Rarely is the behavior we see in class about us. Changing my response to this perspective doesn't mean it doesn't burn a little when a student acts out, but it helps me to ride the waves and respond with kindness. Our students are not just students. They are sons, daughters, grandchildren, brothers, sisters, and friends each with complex lives, experiences and behaviors. Remembering this has helped me to see the people sitting before me. The Climb (we're almost there!) I know that it might feel like a steep hill to climb to break. But, this week more than any, we need to be okay with how our students are surfing and riding the waves. Some of them might be completely geeked and full of excitement. And others might be anticipating a difficult break ahead. Our classrooms must be safe enough so that all of our kids can surf into break. And we need to greet them happily while they do it. Coming in January 2019! New Year, New Posts. Stay tuned for posts about how to talk to parents about supporting writing at home and ready-to-use literacy strategies for tackling challenging texts and topics.

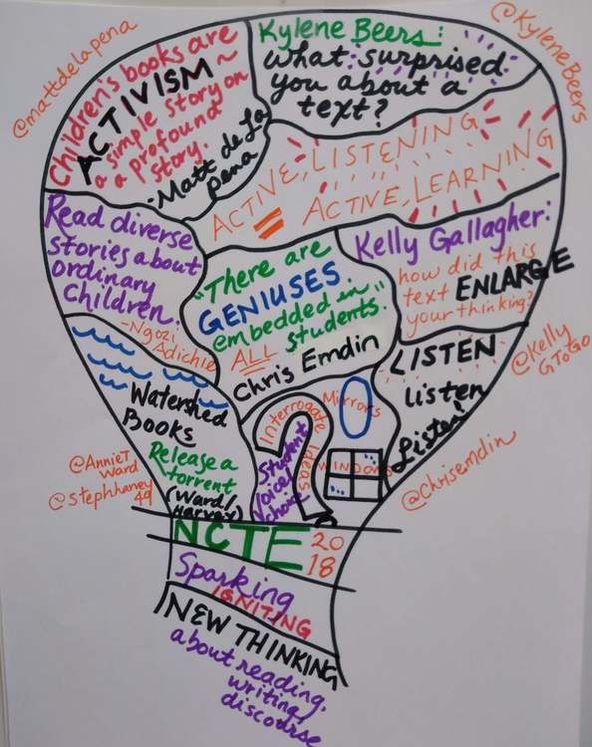

My first NCTE conference left me so energized, I could barely sleep my last night in town with all the new ideas rattling around in my head. Instead of writing a normal post this week, I’m giving you a window into my brain (warning---as I wrote this, I was detoxing from all of the Starbuck’s jet fuel I consumed while at NCTE). All joking aside, in my first session I heard Tanny McGregor present sketchnoting and it launched me back into my own iteration of sketchnoting a light bulb and filling it with all the new ideas that were “enlarging” my thinking (thanks, Kelly Gallagher for this idea). NCTE gave me a window into practices that help readers and writers to discover their authenticity. Here’s the sketchnote that I created on my plane ride home. I included the Twitter handles of voices you won’t regret following on Twitter. (Stay tuned to an upcoming post about how to use sketchnotes and graphic organizers to support thinking routines when reading a text). Teaching is not meant to be practiced in isolation. Listening to new voices affirms, validates and allows us opportunities to constantly evolve as teachers. Thanks, NCTE: You were career-altering!

Good writing starts from good conversation--- at least that’s what one group of my peer writing consultants have to say. This small, yet mighty group of students are earning their English 12 credit through working as peer consultants. We do a lot of careful thinking about how to provide meaningful feedback to writers and to each other. And that’s in part why Verdana, Arial, Roman, Alice and Georgia were so excited to be featured on my blog this week (picking their alias after Google fonts also played a role too). After listening to an end-of-the card marking reflective discussion on their work as consultants, I was reminded of these ideas to spark thinking for a reluctant writer. Start Small Roman had an incredibly challenging experiences with one of his first consults where the writer he worked with basically came up with any and every diversion to derail the writing conference. We now laugh about the fact that at one point he met my eyes from across the room and mouthed “help me.” On top of this, the student’s draft was a treasure map of corrections with a numbered key of all the revisions she wanted to make. Both the writer and Roman were talking in circles as they both tried to make sense of things. Here’s what Roman did: he focused on just one thing. This writer was annoyed that she had to revise an already pretty good piece of writing. And he could tell that. So Roman told her to simply draft a clean copy. And then luckily he was saved by the bell. The next day, he told us that he kept some distance from her, but discovered that when he walked back over, she was ready to talk to him. Turns out the simple advice of just creating a new clean copy opened up space for the two of them to have a conversation about how she could grow her writing. Starting with low effort tasks builds momentum for resistant writers. And as the sage advice goes from Anne Lamott: the best way to write is to go “bird by bird.” Skip the Screen There’s always at least one writer in the room staring blankly at a computer screen during writing workshop. That’s why Alice and Arial explained how their go-to is to hand-write ideas in a notebook before they jump to creating a document. Ariel described how handwriting forces her to slow down and to think differently about her writing. And Alice agrees. He says that it changes how he processes ideas. Arial and Alice didn’t realize this when they brought this up in discussion, but what they are describing is an entire school of thought in composition and brain-based learning theory. So often writers who don’t like writing want to get their work done at rapid speed. Yet, racing through writing can lead students to avoid carefully thinking about what they are trying to say. My consultants agreed that thinking too quickly leads writing to feel manufactured, often replete of author voice. When writers are churning out products rather than thinking about the process, voice and purpose get lost. When writers skip thinking about their writing, they begin to “write in circles” according to Ariel. Share Your Process Consulting is about building a connection with a writer and not giving them all the “corrections” as Georgia wisely noted. All of my consultants agreed that sharing your process and experiences as a writer can be helpful for students who are stuck. In fact--- I have to admit, this piece was born from my own frustrations at starting and stopping this post eight times. And I shared this with my students. For me, blogging has been an opportunity to put myself in my students’ shoes. And from my work with the National Writing Project, I’ve seen how my writing instruction has become stronger from being a writer myself. When teachers write alongside their students, they develop an understanding and empathy of process that they wouldn’t otherwise have. Verdana remarked that students need to understand that there is no one right way. Our role as teachers and consultants is to be a bridge to help a writer discover their process. And the best way to lead students to this discovery is to model our own---to show them many ways to a composition. Truly, talking about being a writer led me to this piece, and there’s nothing like five teenagers excited about picking alias to force me to stick to it. “Trust the Process” The path to a finished product can be a messy process for any writer. When writers are stuck, showing them how to “trust the process” as writing theorist Donald Murray put it best, can help them move beyond their fear that their writing is not enough. Sometimes, the best ways to move a writer through the process are the simplest. Most of all, writers just need to know that there is a reader waiting for their composition to be born.  Sometimes schools launch interventions by buying an expensive program with workbooks, modules and assessments. Yet, these programs cannot replace the work of an intentional and targeted teacher who is responsive to what a student needs. Underperforming students don’t need more worksheets--- they need to be engaged! Here are four characteristics of a “just right” intervention. Contextualized and Individualized Last week, I wrote about how we redesigned interventions at my metro-Detroit high school. All interventions must be high-quality and based on “scientifically-based classroom instruction.” Yet, this does not mean that interventions are canned. The best interventions are customized to the context in which a student learns or to their individual needs. By context, students receive supports and strategies that help them directly manage their coursework. Many of our students enrolled in World History find the course challenging when it comes to reading high-level sources and developing a historical perspective. In order to examine sources and develop such a perspective, students need strategies that help them reconcile the nuances of history. One of my colleagues developed a scaffold (“Yes, No, So” chart) to help students respond to a tricky historical claim. By individualized---it’s focused on the student and meeting them where they are. It doesn’t matter if teaching a student red (Stop and Tell Me Your Claim!), green light (Go find some evidence to prove your claim!) and yellow light (Slow down and explain your evidence!) writing for a paragraph seems out of place at the secondary level. What matters is that the student gets the just right level of instruction to help them grow. Interventions should be designed to help a student thrive within their school. That’s why contextualizing and individualizing the intervention produces strong results. Built on Trust By high school, many students have a lot of baggage about learning, especially those who have found school to be a challenging place. I can sense resistance from a mile away, and that’s why I often begin my work with new students by sharing that we’re the Planet Fitness of classrooms. We’re the No-Judgement Zone. All students thrive when classrooms are safe spaces. To truly learn, all students must admit what they do not yet know or understand. They must feel as though they can be free to express confusion without feeling shame. In short, learning is one of the most vulnerable experiences one will ever face. With all of this considered, it's paramount that students trust their teacher. This is especially the case with striving learners. Building a positive and trusting relationship with your student is the biggest predictor of their success. Supported by Good Questioning I’ve worked with plenty of students who have told me “yes” when I asked---”does that make sense?” and internally had no idea what I had just explained. It’s hard to say “nope, that makes zero sense.” And for some students, saying “yes, got it” is a tactic to evade work because if they’ve “got it” then the conversation is closed. But it doesn’t have to be. Instead of asking a student, “does that make sense?” ask them to re-explain what you’ve just taught them. This is a simple move, but it’s a great way for you to get a read on what they understand. Many times students have a close-to-right answer, but they just need to explain their thinking using discipline-specific wording. Often students who are not engaged learn to say little to nothing in class. And in saying little to nothing, learning becomes passive. By asking students to explain their thinking and reasoning, teachers can help students to grow their vocabulary and comfort level with a subject. Sometimes students need an example of how to answer a question in a discipline-specific way. Providing students with a frame for thinking, like the one shown below, can help students to begin to develop an academic vocabulary and way of communicating. Asking good questions turns once resistant students into active learners. Connected to Parents The MTSS framework views parents as an integral part of the problem solving team because they are your greatest source of information on a student. As interventionists, our team makes a lot of phone calls home to parents. And sometimes we have to make calls when things aren’t going so well. Difficult conversations with parents are intimidating even for the most experienced teacher. One thing that’s helped me is shifting my goal for the call from reporting to gathering. Reporting can create unnecessary tension between students, parents and teachers. But by viewing the conversation as a place to gather information to act on in the classroom, parents and students could easily see that my call was out of support and not retribution. Some questions that help teachers to gather the right kinds of information from parents include:

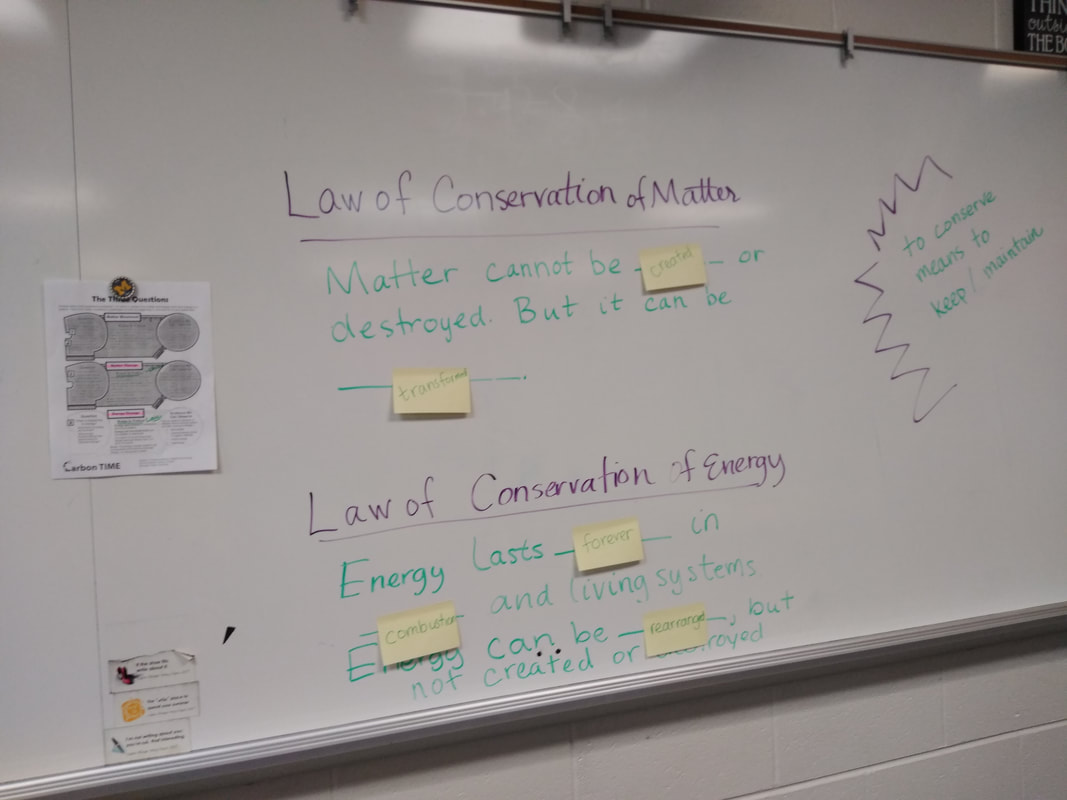

These questions are open-ended and non-threatening. And these questions are all centered on the child. When parents are asked questions like these, they can’t help but see the teacher as a supportive ally in their child’s education. After all, as the proverbial saying goes: it takes a village to raise a child. What matters most The success of an intervention depends on a lot of factors. A teacher’s expertise and skillful use of data are strong components of an intervention. Yet, the most essential factor: connecting with a student and responding to them with the “just right intervention.” A sentence frame to review the Law of Conservation of Matter and Energy for Biology students.

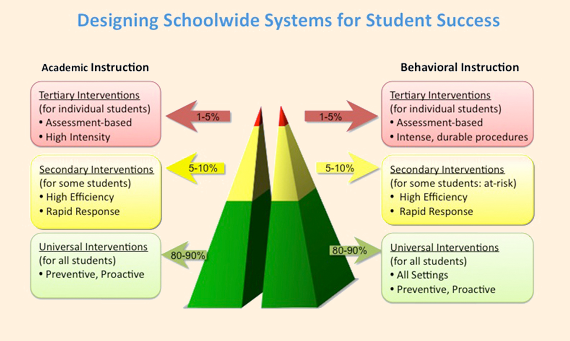

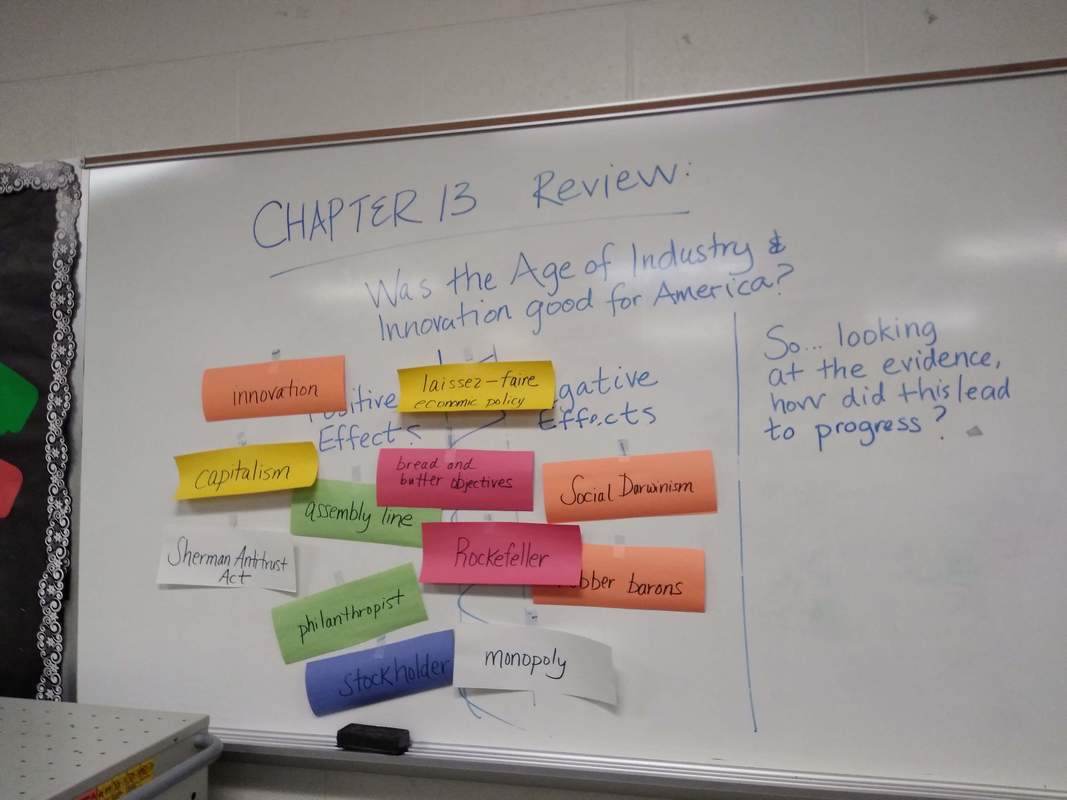

Anyone who has ever worked with striving learners can rattle off a litany of roadblocks. There isn’t enough time to support the student. The student doesn’t want the support. It’s unclear what kind of support the student really needs. Once given the support, the student does not make progress in their core classes. And the list goes on. Supporting learners who resist learning is not for the faint of heart. And that’s why it’s crucial that a strong system is in place to support both students and teachers when achievement and growth does not occur. The Multi-Tiered System of Support model or MTSS is a systematic approach to support all students in ways that accelerate their learning. Based on pyramid of services, (see image) students receive the “just right” level of support depending on their data. MTSS establishes equity; it ensures that instead of everyone getting the same thing, that students receive the kind of the support they need. Credit: https://www.pbis.org/school/mtss Then: The Problem Two years ago, after careful consideration, our school district changed course in how we implemented interventions. To build some context, I teach at a suburban high school in metro-Detroit. For many years, we had relied on standalone English Lab or Math Lab classes to intervene if a student was failing their classes. These courses were meant to provide a skills-based intervention that students would take in addition to their core English or math class. The idea was that they’d take one semester of lab, and all their skill gaps and anti-school behaviors would vanish into thin air. As the English Lab class teacher, I quickly discovered that isolated lessons on skills hardly transferred to other classrooms. I knew that they didn’t just need a worksheet or a scripted lesson. And yet when I shifted my course to supporting them on the work in their classes, the course lacked focus and quickly morphed into a supported study hall. The intervention wasn’t targeted. We also struggled with underutilized data. Students were not scheduled in my room based on assessment data. Instead, students could choose to be in my room, parents could request to take my class or counselors could recommend lab as an option if a student was failing their required ELA class. As a result, many students who needed support also did not receive it. There was not a fluid system that ensured students were receiving the “just right” amount of support. We knew that lab worked in limited cases; it acted as a true tier three intervention for those students who needed that level of support. But for the vast majority of our striving learners, lab was not the intervention they needed. Sometimes growth would happen before the end of a semester, and other times students needed more. We needed a fluid model wherein students could enter and exit at any time to receive the kind of directed support that they need. Now: The Solution In September 2016, our team of one full-time student support coach (me), two math interventionists and two ELA interventionists was charged with implementing a fluid multi-tiered system of support in our building. We abandoned the lab classes, and instead provided support within the context of the classroom. Instead of designing an intervention where students would come to us, we came to them. We formed a problem solving team comprised of interventionists, counselors, social workers, a teacher consultant and administrators. We identify students based on multiple data points: NWEA scores below the 30th percentile, district assessments, transcripts, and state assessments. We triangulate this data and look for patterns that suggest skill deficits. Each year, we examine data to determine who qualifies for our support, and throughout the year, teachers can make referrals for the problem solving team to review. We work with students in their classes, providing push-in support when they are writing, reading or practicing a math skill. And the support isn’t just for ELA and math. Our literacy interventionists provide reading and writing support for students in Social Studies (see image below) and the Sciences. Sometimes we work with students in our office, providing them small-group or one-on-one support. We also pull small groups of students and provide skill-building support during our weekly advisory hour. We develop relationships with teachers that foster collaboration so that when a challenging task is being assigned, we’ve had a chance to build some scaffolds that can support striving learners. Several times a month, we monitor progress by checking student grades to see if they are growing on skills-based assessments. We use this live data to target and direct our intervention to where it’s needed. If a student is not doing well, we provide time to reteach skills in a different way, and we coordinate this support with the teacher. Why Integrating Interventions Works At the heart of our intervention work is our relationships with students and teachers. We make it a point to let students know that they won’t be singled out, that we’ll be discreet when we need to work with them and that most of all, we’ve got their back. Many striving learners feel excluded from school, and our team works to find ways to include them and engage them in the learning process. As for teachers, we get how challenging it is to work with resistant and reluctant learners. We’ve worked to build thoughtful and empathetic relationships with the teachers in our building. At the end of two full years of implementing this program, our data is strong. 80% of our students passed all six classes. We worked with over 100 students last year to support their academic growth, whereas with our old model, we could only serve a fraction of those students. As a whole, our program has successfully prevented students from enrolling in credit recovery, and instead, many of our students have room in their schedules to pursue electives. Beyond the data, one of our students put it best when he said: “[MTSS is] dope. You give us a lot of extra help when we need it. If we are doing bad, you are positive about it. Being positive helps us get our grades up.” And there are few higher forms of praise than being called “dope” by a teenager. A vocabulary activity we planned to review a chapter in U.S. History.

One of the aspects of teaching that I love the most is the ability to start anew each fall. There’s something truly exciting about having a reset and a chance to try out some new ideas. Summer is a chance to slow down our thinking, reflect and gear up for another busy nine months of learning and teaching. School supplies are fresh, the notebooks lay crisply white and if you’re anything like one of my teaching colleagues, your flair pens are organized in ROYGBIV order. Students, whether they are ready or not, arrive and September is a time of transitioning back into a routine. Often we come back that first month with fresh eyes and ideas. But as the year begins, it’s often that some of these ideas lose their hold on us as our minds begin to fill with rosters, grading, activities and managing our own lives outside of school. If you're like me, chances are you are feeling the weight of the school year by October (?!). But it doesn't have to be that way. Here are three ways that I'm going to carry my summer self forward this fall. Write Daily. When I started as a full-time interventionist two years ago, our team wrote reflective entries each time we worked with a student. This act of writing daily observations on students helped us to progress monitor them, but also helped us to refine how we were going to work as a team of literacy interventionists. Writing daily helped me to notice how my students were transforming and growing. Often, these observations were small in nature like “student didn’t recoil at my presence” or “student maintained focus on their writing the entire hour.” But over time, we began to see the cumulative impact of our work with students. A wise professor of mine once said, “small steps make big waves.” Writing daily led me to notice the "waves" in my teaching and this sense of perspective is always rejuvenating to me. Find What’s Good. Last year, I started tracking simple lists of “what’s good?” each day. This emerged from my ROYGBIV teaching colleague who asks this of his students several days a week. On any given day, I was able to find some good things--an inspiring conversation with a colleague, a smile from an otherwise despondent student, listening to an engrossing audio book on my commute. But without this reflection, I sometimes allowed a negative experience with a student to color my entire day. Neuroscientists say that our brains our malleable. We are constantly making new connections—even adults. At times, we are drawn to the negative because it produces stronger emotions, such as anger, frustration or sadness. Mindfulness experts also agree. Some mindfulness practitioners credit the power of simple mantras and conscious breathing with reducing stress and promoting a more positive outlook on challenging situations. And by looking for "what's good?" I found myself open to looking at challenging situations (and at school there's plenty!) with a more positive lens. Practice Self-Care. As the mom of three growing boys all under the age of ten, I read a lot of parenting books, blogs and articles. I’m also of the mindset that my kids are only young once, and I often say “yes” before I really think about how a new commitment is going to fit into my life. Though well-intentioned, my over-scheduling often leads me to burn out—both as a teacher and a mom. There’s a familiar metaphor on many parenting (and teaching) blogs about who gets the air mask first on an airplane in case of an emergency—the kids or the parents. Flight attendants tell parents to get air first so that they can help others. If we can’t breathe surely those that we care for won’t be able to either! This goes for parenting, teaching or just about any relationship. So, this fall, one new thing that I pledge to start is taking time each day to exhale, exercise and do something that brings me joy—whether it’s a good book, chasing my kids down a hill, or a hike in the woods with my husband. Remember that the year is still young. If you're already feeling turbulence, it's just a chance to regain your footing. Put your mask on first! |

AuthorLauren Nizol is a literacy interventionist, writing center director, and National Writing Project Teacher Consultant who loves books and takes too many pictures of trees when heading for the woods with her family. Archives

September 2020

Categories |

Photos from wuestenigel (CC BY 2.0), shixart1985, lorenkerns, wuestenigel (CC BY 2.0), hans-johnson

RSS Feed

RSS Feed