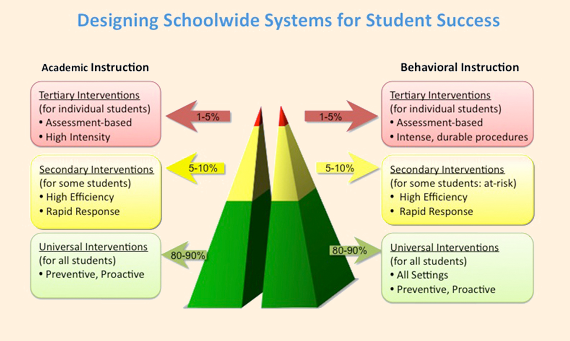

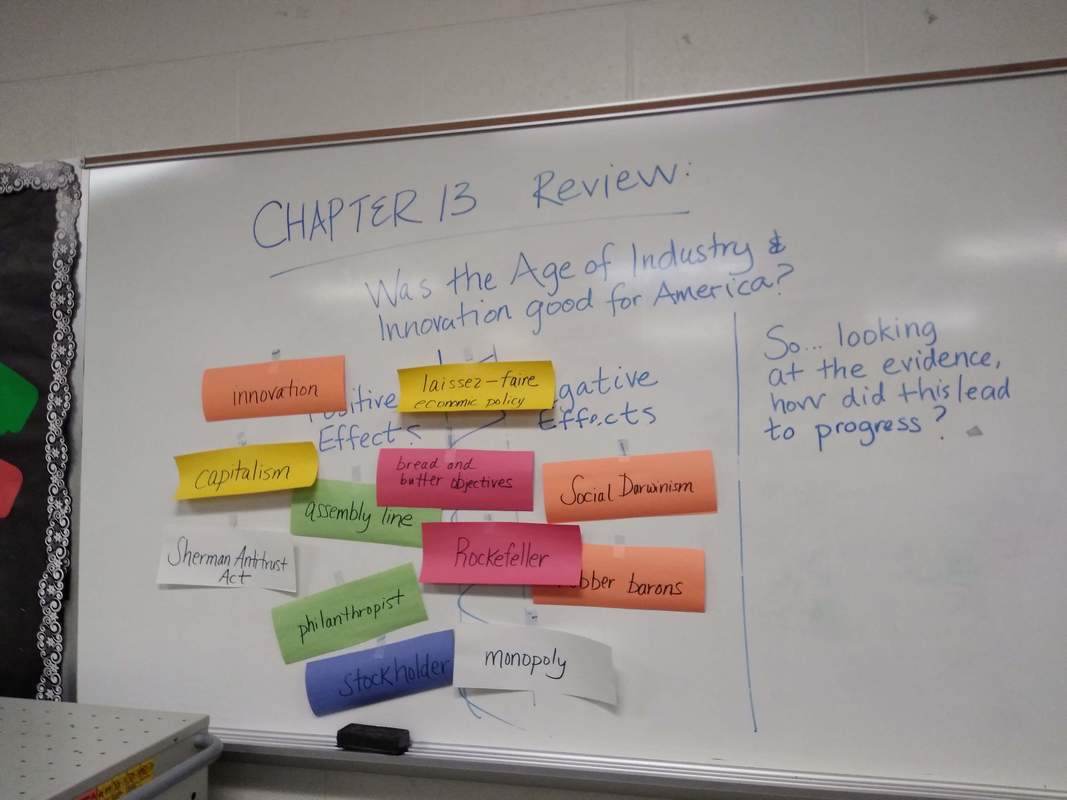

Anyone who has ever worked with striving learners can rattle off a litany of roadblocks. There isn’t enough time to support the student. The student doesn’t want the support. It’s unclear what kind of support the student really needs. Once given the support, the student does not make progress in their core classes. And the list goes on. Supporting learners who resist learning is not for the faint of heart. And that’s why it’s crucial that a strong system is in place to support both students and teachers when achievement and growth does not occur. The Multi-Tiered System of Support model or MTSS is a systematic approach to support all students in ways that accelerate their learning. Based on pyramid of services, (see image) students receive the “just right” level of support depending on their data. MTSS establishes equity; it ensures that instead of everyone getting the same thing, that students receive the kind of the support they need. Credit: https://www.pbis.org/school/mtss Then: The Problem Two years ago, after careful consideration, our school district changed course in how we implemented interventions. To build some context, I teach at a suburban high school in metro-Detroit. For many years, we had relied on standalone English Lab or Math Lab classes to intervene if a student was failing their classes. These courses were meant to provide a skills-based intervention that students would take in addition to their core English or math class. The idea was that they’d take one semester of lab, and all their skill gaps and anti-school behaviors would vanish into thin air. As the English Lab class teacher, I quickly discovered that isolated lessons on skills hardly transferred to other classrooms. I knew that they didn’t just need a worksheet or a scripted lesson. And yet when I shifted my course to supporting them on the work in their classes, the course lacked focus and quickly morphed into a supported study hall. The intervention wasn’t targeted. We also struggled with underutilized data. Students were not scheduled in my room based on assessment data. Instead, students could choose to be in my room, parents could request to take my class or counselors could recommend lab as an option if a student was failing their required ELA class. As a result, many students who needed support also did not receive it. There was not a fluid system that ensured students were receiving the “just right” amount of support. We knew that lab worked in limited cases; it acted as a true tier three intervention for those students who needed that level of support. But for the vast majority of our striving learners, lab was not the intervention they needed. Sometimes growth would happen before the end of a semester, and other times students needed more. We needed a fluid model wherein students could enter and exit at any time to receive the kind of directed support that they need. Now: The Solution In September 2016, our team of one full-time student support coach (me), two math interventionists and two ELA interventionists was charged with implementing a fluid multi-tiered system of support in our building. We abandoned the lab classes, and instead provided support within the context of the classroom. Instead of designing an intervention where students would come to us, we came to them. We formed a problem solving team comprised of interventionists, counselors, social workers, a teacher consultant and administrators. We identify students based on multiple data points: NWEA scores below the 30th percentile, district assessments, transcripts, and state assessments. We triangulate this data and look for patterns that suggest skill deficits. Each year, we examine data to determine who qualifies for our support, and throughout the year, teachers can make referrals for the problem solving team to review. We work with students in their classes, providing push-in support when they are writing, reading or practicing a math skill. And the support isn’t just for ELA and math. Our literacy interventionists provide reading and writing support for students in Social Studies (see image below) and the Sciences. Sometimes we work with students in our office, providing them small-group or one-on-one support. We also pull small groups of students and provide skill-building support during our weekly advisory hour. We develop relationships with teachers that foster collaboration so that when a challenging task is being assigned, we’ve had a chance to build some scaffolds that can support striving learners. Several times a month, we monitor progress by checking student grades to see if they are growing on skills-based assessments. We use this live data to target and direct our intervention to where it’s needed. If a student is not doing well, we provide time to reteach skills in a different way, and we coordinate this support with the teacher. Why Integrating Interventions Works At the heart of our intervention work is our relationships with students and teachers. We make it a point to let students know that they won’t be singled out, that we’ll be discreet when we need to work with them and that most of all, we’ve got their back. Many striving learners feel excluded from school, and our team works to find ways to include them and engage them in the learning process. As for teachers, we get how challenging it is to work with resistant and reluctant learners. We’ve worked to build thoughtful and empathetic relationships with the teachers in our building. At the end of two full years of implementing this program, our data is strong. 80% of our students passed all six classes. We worked with over 100 students last year to support their academic growth, whereas with our old model, we could only serve a fraction of those students. As a whole, our program has successfully prevented students from enrolling in credit recovery, and instead, many of our students have room in their schedules to pursue electives. Beyond the data, one of our students put it best when he said: “[MTSS is] dope. You give us a lot of extra help when we need it. If we are doing bad, you are positive about it. Being positive helps us get our grades up.” And there are few higher forms of praise than being called “dope” by a teenager. A vocabulary activity we planned to review a chapter in U.S. History.

1 Comment

|

AuthorLauren Nizol is a literacy interventionist, writing center director, and National Writing Project Teacher Consultant who loves books and takes too many pictures of trees when heading for the woods with her family. Archives

September 2020

Categories |

Photos from wuestenigel (CC BY 2.0), shixart1985, lorenkerns, wuestenigel (CC BY 2.0), hans-johnson

RSS Feed

RSS Feed