Sometimes schools launch interventions by buying an expensive program with workbooks, modules and assessments. Yet, these programs cannot replace the work of an intentional and targeted teacher who is responsive to what a student needs. Underperforming students don’t need more worksheets--- they need to be engaged! Here are four characteristics of a “just right” intervention. Contextualized and Individualized Last week, I wrote about how we redesigned interventions at my metro-Detroit high school. All interventions must be high-quality and based on “scientifically-based classroom instruction.” Yet, this does not mean that interventions are canned. The best interventions are customized to the context in which a student learns or to their individual needs. By context, students receive supports and strategies that help them directly manage their coursework. Many of our students enrolled in World History find the course challenging when it comes to reading high-level sources and developing a historical perspective. In order to examine sources and develop such a perspective, students need strategies that help them reconcile the nuances of history. One of my colleagues developed a scaffold (“Yes, No, So” chart) to help students respond to a tricky historical claim. By individualized---it’s focused on the student and meeting them where they are. It doesn’t matter if teaching a student red (Stop and Tell Me Your Claim!), green light (Go find some evidence to prove your claim!) and yellow light (Slow down and explain your evidence!) writing for a paragraph seems out of place at the secondary level. What matters is that the student gets the just right level of instruction to help them grow. Interventions should be designed to help a student thrive within their school. That’s why contextualizing and individualizing the intervention produces strong results. Built on Trust By high school, many students have a lot of baggage about learning, especially those who have found school to be a challenging place. I can sense resistance from a mile away, and that’s why I often begin my work with new students by sharing that we’re the Planet Fitness of classrooms. We’re the No-Judgement Zone. All students thrive when classrooms are safe spaces. To truly learn, all students must admit what they do not yet know or understand. They must feel as though they can be free to express confusion without feeling shame. In short, learning is one of the most vulnerable experiences one will ever face. With all of this considered, it's paramount that students trust their teacher. This is especially the case with striving learners. Building a positive and trusting relationship with your student is the biggest predictor of their success. Supported by Good Questioning I’ve worked with plenty of students who have told me “yes” when I asked---”does that make sense?” and internally had no idea what I had just explained. It’s hard to say “nope, that makes zero sense.” And for some students, saying “yes, got it” is a tactic to evade work because if they’ve “got it” then the conversation is closed. But it doesn’t have to be. Instead of asking a student, “does that make sense?” ask them to re-explain what you’ve just taught them. This is a simple move, but it’s a great way for you to get a read on what they understand. Many times students have a close-to-right answer, but they just need to explain their thinking using discipline-specific wording. Often students who are not engaged learn to say little to nothing in class. And in saying little to nothing, learning becomes passive. By asking students to explain their thinking and reasoning, teachers can help students to grow their vocabulary and comfort level with a subject. Sometimes students need an example of how to answer a question in a discipline-specific way. Providing students with a frame for thinking, like the one shown below, can help students to begin to develop an academic vocabulary and way of communicating. Asking good questions turns once resistant students into active learners. Connected to Parents The MTSS framework views parents as an integral part of the problem solving team because they are your greatest source of information on a student. As interventionists, our team makes a lot of phone calls home to parents. And sometimes we have to make calls when things aren’t going so well. Difficult conversations with parents are intimidating even for the most experienced teacher. One thing that’s helped me is shifting my goal for the call from reporting to gathering. Reporting can create unnecessary tension between students, parents and teachers. But by viewing the conversation as a place to gather information to act on in the classroom, parents and students could easily see that my call was out of support and not retribution. Some questions that help teachers to gather the right kinds of information from parents include:

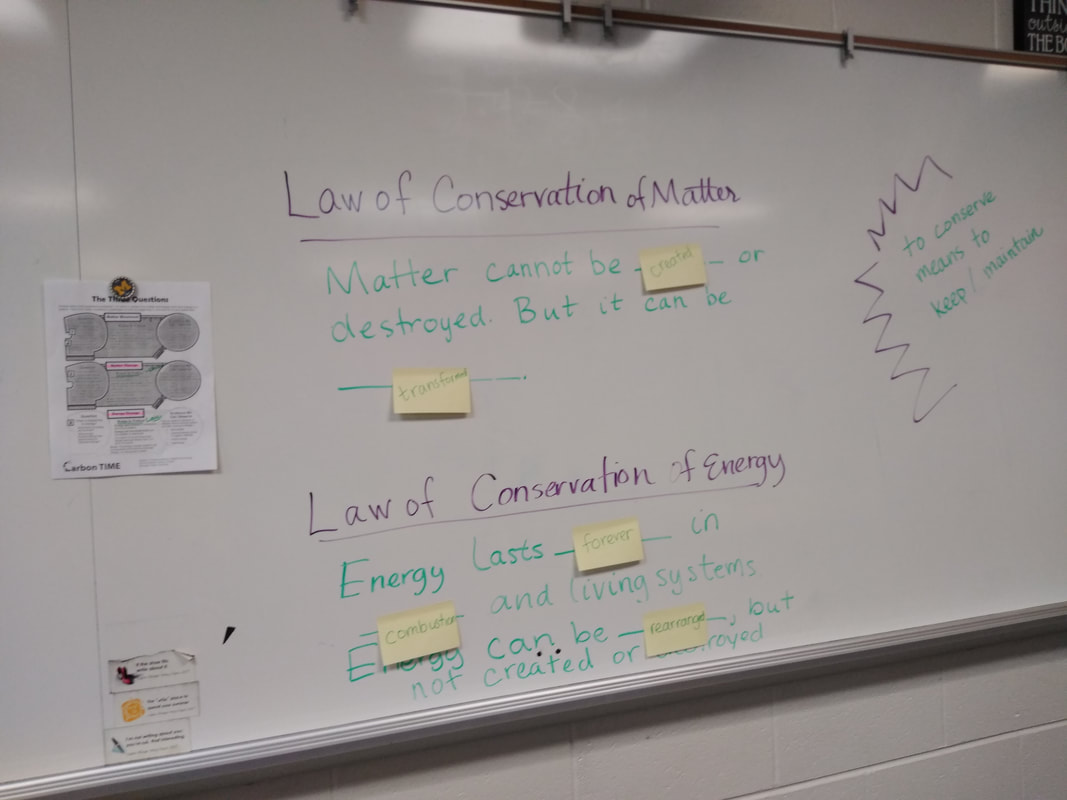

These questions are open-ended and non-threatening. And these questions are all centered on the child. When parents are asked questions like these, they can’t help but see the teacher as a supportive ally in their child’s education. After all, as the proverbial saying goes: it takes a village to raise a child. What matters most The success of an intervention depends on a lot of factors. A teacher’s expertise and skillful use of data are strong components of an intervention. Yet, the most essential factor: connecting with a student and responding to them with the “just right intervention.” A sentence frame to review the Law of Conservation of Matter and Energy for Biology students.

1 Comment

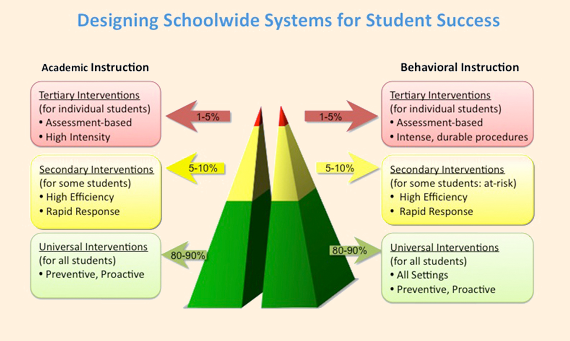

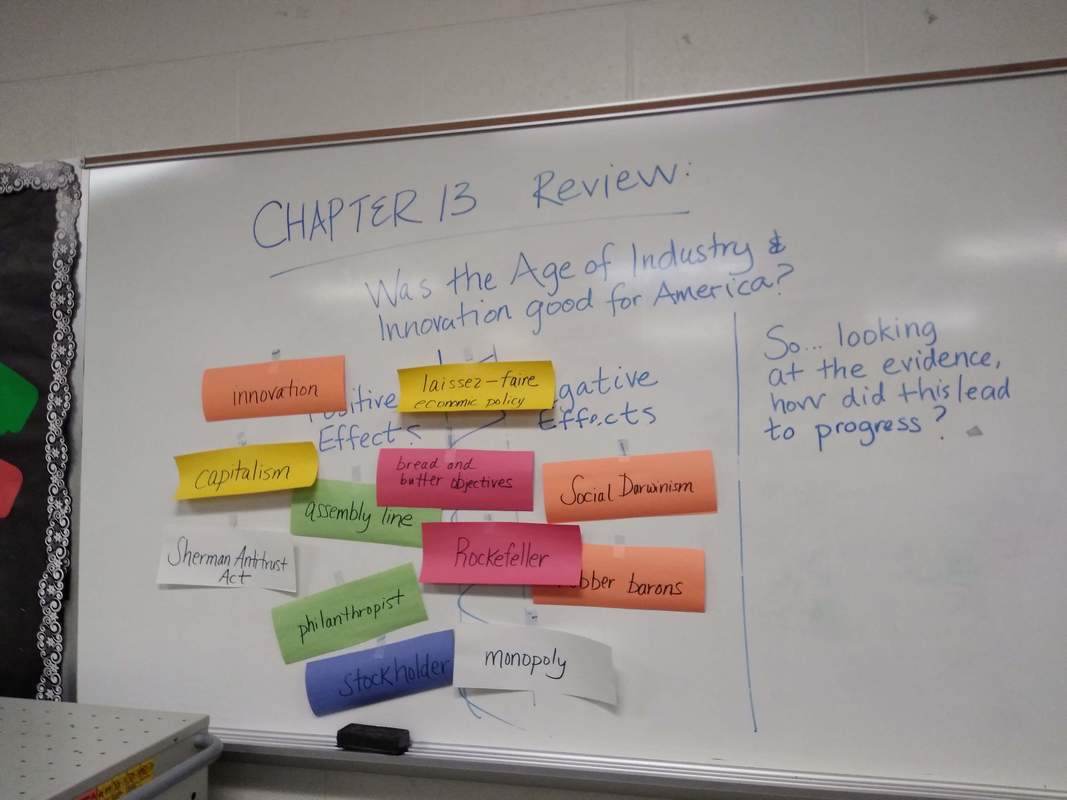

Anyone who has ever worked with striving learners can rattle off a litany of roadblocks. There isn’t enough time to support the student. The student doesn’t want the support. It’s unclear what kind of support the student really needs. Once given the support, the student does not make progress in their core classes. And the list goes on. Supporting learners who resist learning is not for the faint of heart. And that’s why it’s crucial that a strong system is in place to support both students and teachers when achievement and growth does not occur. The Multi-Tiered System of Support model or MTSS is a systematic approach to support all students in ways that accelerate their learning. Based on pyramid of services, (see image) students receive the “just right” level of support depending on their data. MTSS establishes equity; it ensures that instead of everyone getting the same thing, that students receive the kind of the support they need. Credit: https://www.pbis.org/school/mtss Then: The Problem Two years ago, after careful consideration, our school district changed course in how we implemented interventions. To build some context, I teach at a suburban high school in metro-Detroit. For many years, we had relied on standalone English Lab or Math Lab classes to intervene if a student was failing their classes. These courses were meant to provide a skills-based intervention that students would take in addition to their core English or math class. The idea was that they’d take one semester of lab, and all their skill gaps and anti-school behaviors would vanish into thin air. As the English Lab class teacher, I quickly discovered that isolated lessons on skills hardly transferred to other classrooms. I knew that they didn’t just need a worksheet or a scripted lesson. And yet when I shifted my course to supporting them on the work in their classes, the course lacked focus and quickly morphed into a supported study hall. The intervention wasn’t targeted. We also struggled with underutilized data. Students were not scheduled in my room based on assessment data. Instead, students could choose to be in my room, parents could request to take my class or counselors could recommend lab as an option if a student was failing their required ELA class. As a result, many students who needed support also did not receive it. There was not a fluid system that ensured students were receiving the “just right” amount of support. We knew that lab worked in limited cases; it acted as a true tier three intervention for those students who needed that level of support. But for the vast majority of our striving learners, lab was not the intervention they needed. Sometimes growth would happen before the end of a semester, and other times students needed more. We needed a fluid model wherein students could enter and exit at any time to receive the kind of directed support that they need. Now: The Solution In September 2016, our team of one full-time student support coach (me), two math interventionists and two ELA interventionists was charged with implementing a fluid multi-tiered system of support in our building. We abandoned the lab classes, and instead provided support within the context of the classroom. Instead of designing an intervention where students would come to us, we came to them. We formed a problem solving team comprised of interventionists, counselors, social workers, a teacher consultant and administrators. We identify students based on multiple data points: NWEA scores below the 30th percentile, district assessments, transcripts, and state assessments. We triangulate this data and look for patterns that suggest skill deficits. Each year, we examine data to determine who qualifies for our support, and throughout the year, teachers can make referrals for the problem solving team to review. We work with students in their classes, providing push-in support when they are writing, reading or practicing a math skill. And the support isn’t just for ELA and math. Our literacy interventionists provide reading and writing support for students in Social Studies (see image below) and the Sciences. Sometimes we work with students in our office, providing them small-group or one-on-one support. We also pull small groups of students and provide skill-building support during our weekly advisory hour. We develop relationships with teachers that foster collaboration so that when a challenging task is being assigned, we’ve had a chance to build some scaffolds that can support striving learners. Several times a month, we monitor progress by checking student grades to see if they are growing on skills-based assessments. We use this live data to target and direct our intervention to where it’s needed. If a student is not doing well, we provide time to reteach skills in a different way, and we coordinate this support with the teacher. Why Integrating Interventions Works At the heart of our intervention work is our relationships with students and teachers. We make it a point to let students know that they won’t be singled out, that we’ll be discreet when we need to work with them and that most of all, we’ve got their back. Many striving learners feel excluded from school, and our team works to find ways to include them and engage them in the learning process. As for teachers, we get how challenging it is to work with resistant and reluctant learners. We’ve worked to build thoughtful and empathetic relationships with the teachers in our building. At the end of two full years of implementing this program, our data is strong. 80% of our students passed all six classes. We worked with over 100 students last year to support their academic growth, whereas with our old model, we could only serve a fraction of those students. As a whole, our program has successfully prevented students from enrolling in credit recovery, and instead, many of our students have room in their schedules to pursue electives. Beyond the data, one of our students put it best when he said: “[MTSS is] dope. You give us a lot of extra help when we need it. If we are doing bad, you are positive about it. Being positive helps us get our grades up.” And there are few higher forms of praise than being called “dope” by a teenager. A vocabulary activity we planned to review a chapter in U.S. History.

One of the aspects of teaching that I love the most is the ability to start anew each fall. There’s something truly exciting about having a reset and a chance to try out some new ideas. Summer is a chance to slow down our thinking, reflect and gear up for another busy nine months of learning and teaching. School supplies are fresh, the notebooks lay crisply white and if you’re anything like one of my teaching colleagues, your flair pens are organized in ROYGBIV order. Students, whether they are ready or not, arrive and September is a time of transitioning back into a routine. Often we come back that first month with fresh eyes and ideas. But as the year begins, it’s often that some of these ideas lose their hold on us as our minds begin to fill with rosters, grading, activities and managing our own lives outside of school. If you're like me, chances are you are feeling the weight of the school year by October (?!). But it doesn't have to be that way. Here are three ways that I'm going to carry my summer self forward this fall. Write Daily. When I started as a full-time interventionist two years ago, our team wrote reflective entries each time we worked with a student. This act of writing daily observations on students helped us to progress monitor them, but also helped us to refine how we were going to work as a team of literacy interventionists. Writing daily helped me to notice how my students were transforming and growing. Often, these observations were small in nature like “student didn’t recoil at my presence” or “student maintained focus on their writing the entire hour.” But over time, we began to see the cumulative impact of our work with students. A wise professor of mine once said, “small steps make big waves.” Writing daily led me to notice the "waves" in my teaching and this sense of perspective is always rejuvenating to me. Find What’s Good. Last year, I started tracking simple lists of “what’s good?” each day. This emerged from my ROYGBIV teaching colleague who asks this of his students several days a week. On any given day, I was able to find some good things--an inspiring conversation with a colleague, a smile from an otherwise despondent student, listening to an engrossing audio book on my commute. But without this reflection, I sometimes allowed a negative experience with a student to color my entire day. Neuroscientists say that our brains our malleable. We are constantly making new connections—even adults. At times, we are drawn to the negative because it produces stronger emotions, such as anger, frustration or sadness. Mindfulness experts also agree. Some mindfulness practitioners credit the power of simple mantras and conscious breathing with reducing stress and promoting a more positive outlook on challenging situations. And by looking for "what's good?" I found myself open to looking at challenging situations (and at school there's plenty!) with a more positive lens. Practice Self-Care. As the mom of three growing boys all under the age of ten, I read a lot of parenting books, blogs and articles. I’m also of the mindset that my kids are only young once, and I often say “yes” before I really think about how a new commitment is going to fit into my life. Though well-intentioned, my over-scheduling often leads me to burn out—both as a teacher and a mom. There’s a familiar metaphor on many parenting (and teaching) blogs about who gets the air mask first on an airplane in case of an emergency—the kids or the parents. Flight attendants tell parents to get air first so that they can help others. If we can’t breathe surely those that we care for won’t be able to either! This goes for parenting, teaching or just about any relationship. So, this fall, one new thing that I pledge to start is taking time each day to exhale, exercise and do something that brings me joy—whether it’s a good book, chasing my kids down a hill, or a hike in the woods with my husband. Remember that the year is still young. If you're already feeling turbulence, it's just a chance to regain your footing. Put your mask on first! |

AuthorLauren Nizol is a literacy interventionist, writing center director, and National Writing Project Teacher Consultant who loves books and takes too many pictures of trees when heading for the woods with her family. Archives

September 2020

Categories |

Photos from wuestenigel (CC BY 2.0), shixart1985, lorenkerns, wuestenigel (CC BY 2.0), hans-johnson

RSS Feed

RSS Feed